I recently completed four weeks of clinical work at the Northern Navajo Medical Center, a hospital and clinic owned by the Indian Health Services. The center is located the small town of Shiprock and surrounded by the Four Corners region, a both vast and beautiful part of the country. My time there was highly enriching, personally and professionally. I had the privilege of working with a wonderful and gracious patient population whose history is both sad and interesting, and I was challenged by their medical complexity. I also encountered some of the unique struggles associated with practicing medicine in a rural, under-resourced setting.

Being in such a remote location constantly challenged me to think about the implications of my medical decisions. One of the things that has continued to resonate with me was how often geography played into the nuances of our medical management. One of the more vivid interactions I had occurred in hepatology clinic with a patient who at first glance seemed very disconnected with his care. He had missed numerous visits prior to this appointment, and this time he arrived twenty minutes late. As we were talking, he told me that he had walked two hours to get to this appointment. Two hours for a fifteen minute visit, and that’s one way. I’ve seen some shocking things during residency. But there was something about his statement that was almost more jolting than those things. It wasn’t at all what I had expected to hear. I felt guilty about my slight annoyance when he was late. I also realized that with every patient at Shiprock, it was crucial to understand physically where they were coming from and where they would go after I sent them away. From deciding whether or not to admit them to making sure they got their mammogram in the appropriate location, it was always important to consider the geographic context.

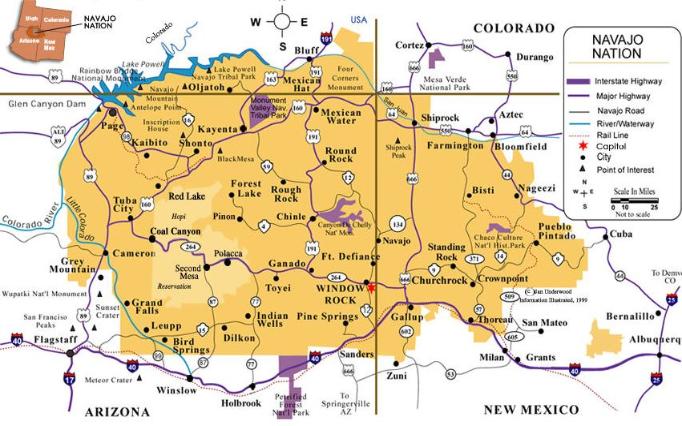

The Navajo reservation is a sizeable amount of land. It’s the largest reservation in the United States and encompasses over 27,000 square miles. There are about 300,000 members of the Navajo Nation, and half of them live on the reservation. According to the 2010 census, the median income of the Navajo Nation is $20,000, and 43% of members live below the poverty line.

Although the Navajo reservation is unique in that much of it lies on ancestral Navajo land, there is a sad and bloody history behind how it officially was deemed Navajo territory. The Navajos first encountered the Spanish in the late 1500s. For the roughly 300 years of coexistence of the two groups, there was hardly a peaceful period. In 1821, New Mexico gained its independence from the Spanish. Despite this change in leadership, skirmishes and raids between the Navajo and other settlers continued. By 1846, the United States had gained nominal control of New Mexico, and the Bear Springs Treaty was an attempt to make peace. Despite adherence of the most prominent Navajo leaders to this treaty, younger Navajo raiders continued to attack New Mexican settlements. Three years later, one of the most respected Navajo leaders, Chief Nabona, met with an American Colonel to attempt another peace treaty. Instead of a settlement, the encounter ended with American soldiers shooting and scalping Chief Nabona. Anger over this incident prompted the more war-oriented leaders of the Navajo to continue escalating violence.

In 1862, General James Carleton became head of the American troops in New Mexico. He thought (wrongfully) that all Navajo were violent and warlike and felt that the best solution was to confine them at Fort Sumner, an area on the Pecos River that the Navajo people called “Hweeldi.” The Navajo, however, refused to give up their land in order to move to this unfamiliar area. So General Carleton resorted to brutal methods in hopes of forcing compliance. He and his men burned towns, killed livestock, and destroyed fields.

In the dead of winter, these ruthless tactics worked. Many of the Navajo felt they had to surrender in hopes of staving off starvation and freezing temperatures. The subsequent 300-mile herding of the Navajo to Fort Sumner is called the “Long Walk.” It was completely inhumane. Many Navajo died of starvation and fatigue, and others were shot and killed if they couldn’t keep pace. At the end of it, over 8000 Navajo were crowded onto an internment camp of a meager 40 square miles. Conditions were decrepit, and both food and water were insufficient. Eventually, the Treaty of 1868 was signed. It allowed the Navajo to reclaim some of their ancestral lands, and they were finally able to make the “Long Walk” home.

My patient’s trek to his appointment wasn’t three hundred miles, but it was still an impressive distance. The struggles he faced to transport himself to appointments and to the pharmacy inherently affected his medical care. Similarly, the struggles that the Navajo people underwent to reclaim their rightful land have helped mold their cultural identity. Medicine cares for individuals, and remembering each patient’s unique cultural identity is an integral part of their medical care. Whether it involves understanding their ethnic background or asking where they live, their story should influence both how we empathize with them and how we determine the most appropriate clinical management.

Andrea, great post. That sort of insight into a patient’s lived experience underlies all equity efforts, I believe – you need to understand what others are working through, or against, before you have a partial grasp of what system changes will best support their efforts. I’m glad you had a good rotation, and hope that we’ll have many more BMC trainees heading out to IHS sites in the years to come!